Nestled in the green landscape of Oregon is what is said to be the most authentic Japanese-style garden outside of Japan—the Portland Japanese Garden, visited by some 300,000 people annually. On a recent visit to Japan, its curator, Uchiyama Sadafumi, spoke with us about the changing history of Japanese gardens in the United States and their new potential. He also shared with us another purpose of his visit—the return to Japan of shrine gates carried across the Pacific to the shores of Oregon after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

[November 2014]

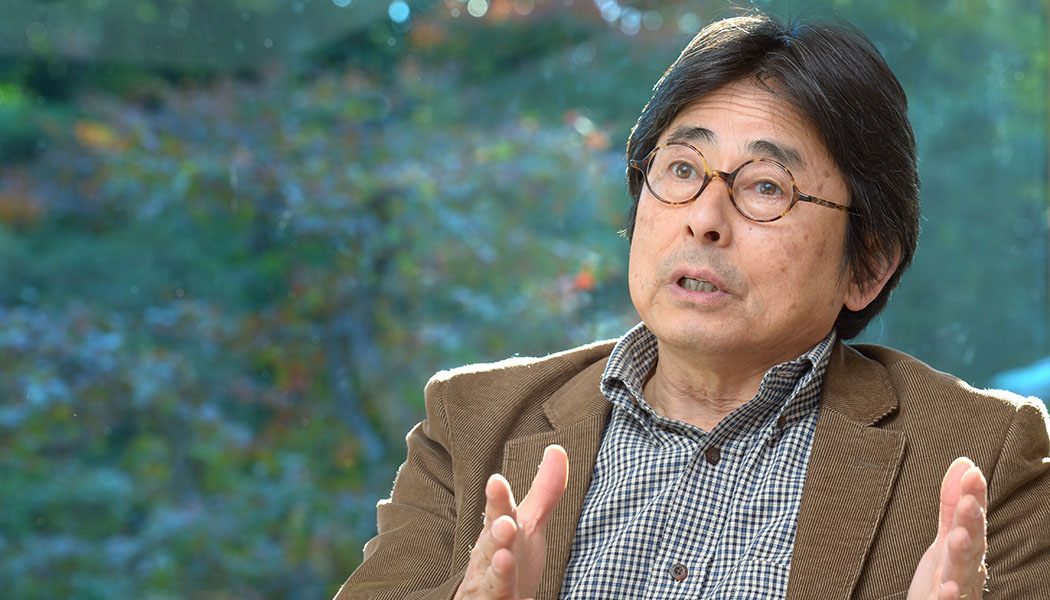

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1955, Uchiyama grew up in a family of professional gardeners active since 1909, where from childhood he received training in the craft. After doing developmental assistance work in Tanzania and Yemen, he went to the United States in 1988, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in landscape architecture at the University of Illinois. Making full use of his experience of gardens in both Japan and the US, he has involved himself in a wide range of work, from private gardens to public projects.

I believe the Portland Japanese Garden is one of the most authentic Japanese gardens outside Japan.

Opened in 1967, the 5.5 acre site contains five gardens in distinct styles, including traditional hiraniwa (flat garden) and karesansui (sand and stone) gardens. We host a variety of Japanese cultural events, art exhibitions, and workshops, and at this point receive nearly 300,000 visitors annually. I’ve been curator since 2008, supervising the maintenance of the garden, training local staff, and conducting educational activities to promote a better understanding of Japanese gardens and the culture that inspired them.

How are Japanese gardens seen in the US?

Japanese gardens were first introduced to the US more than 120 years ago, around the time when the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago in 1893. They were part of a diplomatic effort to introduce Japanese culture to the American public. The exposition encouraged a number of wealthy businessmen to build Japanese gardens for their mansions or estates.

Then, after World War II, a number of Japanese and American cities formed sister-city relationships, and Japanese gardens were created as a symbol of friendship. Now there are more than 250 public Japanese gardens in North America, as far as I know. Maintaining such gardens requires commitment and resources and is not an easy task. So the fact that Japanese gardens have survived in such numbers means that they have a special place in American hearts.

©Stephen Bridges

©David Cobb

©David Cobb

Japanese gardens have a variety of types, and the design and philosophy behind them are quite complex.

Any highly refined art has aspects that are difficult to appreciate, but I believe that gardens are not as hard to explain as they are made out to be. Basically, the everyday aesthetic of the Japanese people—caring for things, keeping things neat and clean—developed through art into a refined system of values that included ideals such as wabi and sabi (rustic simplicity) and yugen (the sublime). So it makes sense, when speaking about gardens, not to launch into a discussion of concepts like yugen right away, but to start instead at an easier level—the experience of everyday life.

Of course there are major cultural differences, born out of the experience of growing up in very different cultural and physical environments. It is not surprising that for Americans to really appreciate, for example, ka-cho-fu-getsu [the traditional themes of natural beauty in Japanese aesthetics] might take several generations. That sounds like a long time, but I think of Japanese gardens in the perspective of a thousand years. If you think about it, we pride ourselves in Japan for being the center of Zen Buddhism and its traditions, but these things came to us originally from India, then China. It took more than a thousand years for them to reach their full fruition in Japan.

The Japanese garden was born some 1,200 years ago, and we’ve carefully nurtured it for all these centuries—but perhaps Japan just happens to be its point of origin, and it is really destined to be shared with the world as a whole. So it is important to realize that the Japanese garden is not a garden by and for Japanese people only, but embodies a universality that transcends cultural boundaries.

You mean that we ought to look at culture from a broad temporal and geographic perspective, and not confine it to a particular country or period.

Well, certainly when you look at a Japanese garden you think it is beautiful or interesting. But that’s just the entry point—what you are feeling deep in your heart is something more essential and universal, I believe. For example, my wife practices yoga. The point of entry is different, but ultimately gardens and yoga are headed in the same direction.

And if that is true, then there are probably millions of people in America and elsewhere headed in that direction as well. In this sense I see the Japanese garden not as an “object” but as a spirit, a matter of the heart. People are in their spiritual quest by way of yoga, or zazen, or perhaps Japanese gardens. What people have looked for in the Japanese garden may have changed over time, but there is definitely something about its forms and philosophy that has continued to be relevant to their life for more than a millenium.

You are involved in training Americans to be professional Japanese gardeners. How is that process different from what it might be in Japan?

As gardeners, they are taught the same set of skills that we teach in Japan. What’s difficult to teach is the intangibles, the “heart” part. Or, call it “fudo,” the cultural environment and the “spirit” of the Japanese garden. You can export Japanese stone lanterns and rocks and transfer skills overseas, but you can’t really bring this spirit over the Pacific Ocean.

So to enable these American gardeners to have similar experience that would take the place of growing up in the Japanese cultural environment, we encourage them to gain a holistic experience with Japanese culture and aesthetics—the tea ceremony, flower arrangement—so they get a feel for its cultural boundaries. It is also very important to give the students as much verbal explanation of everything as I can. Teaching by showing examples just doesn’t work overseas. I learned that in Tanzania and Yemen.

©Jonathan Ley

©Jonathan Ley

Why did you go to Tanzania and Yemen?

When I graduated from high school, I was determined not to continue in the family trade [laughs]. I’d begun helping with the garden work from about the age of 10, so by that time I had learned pretty much everything required as a professional gardener. But there were lots of lines of work that were more exciting than being a gardener. I wanted some good reason for leaving home, so I went to Tanzania with the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers. In Tanzania, deforestation resulting from people harvesting firewood had become a serious social problem, and I worked for reforestation projects. Then I made my next escape by going to Yemen as a specialist with what is now the Japan International Cooperation Agency. But what I really learned by going overseas was how little I knew.

So, at the age of 32, I entered the University of Illinois to begin the serious study of landscape architecture. The first two years were pure hell [laughs]. My professors knew I was a third-generation Japanese gardener, and asked me all sorts of questions. But when I tried to explain things to them, I actually couldn’t. I may have put in my time learning the craft, but I didn’t understand its history and deeper meaning. It was in America that I realized how profound the art of the Japanese garden is.

I understand you are now trying to revitalize communication between Japanese and American garden specialists?

Yes. In the 25 years of my living in the US, I have seen many Japanese gardens struggling with maintenance and management because of a lack of skilled professionals. So in 2012 we created the North American Japanese Garden Association to serve as a major conduit linking gardening circles in Japan and the US. Now, as the next step, at the Portland Japanese Garden we are creating the International Institute for Japanese Garden Arts and Culture to provide a venue for the comprehensive study of these subjects and to enable people to use our network of contacts to go to Japan for further study.

One of your reasons for this visit to Japan is the shrine gates that were swept away by the tsunami following the 2011 earthquake and washed ashore on the Oregon coast.

In March 2013, almost exactly two years after the earthquake, pieces of two gates from Shinto shrines washed ashore on the Oregon coast and became local news. When the first one was discovered, I was actually the one who identified it, from a photo that had been e-mailed to a friend of mine who happened to be visiting our garden. He showed it to me and right away I knew it was the lintel (top beam called “kasagi”) of a shrine gate, or torii.

Then, about a month later, a farming couple discovered the second piece, also a lintel. The husband had studied abroad in Japan and immediately recognized it was part of a torii. On this particular piece, the portion known as the gakutsuka survived, where the names of donors are inscribed. After many conversations in the Japan-related community in Oregon, the Portland Japanese Garden was asked to help find where it had come from and, hopefully, to return it to the place and people which it belonged to.

Recovery operations for the kasagi beam in Oregon.

What kind of clues did you have?

Not much beyond the name of a donor and the year of the building. I went first to the cities of Rikuzentakata and Kesennuma, where I talked with some cab drivers and asked passersby for information. Then the story was picked up by NHK News, and a variety of people offered help in the search. But we found no clues in the three prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima. It was only when the search expanded to the city of Hachinohe in Aomori Prefecture that we finally connected with the local fishermen who dedicated the torii.

We learned from one of them, Takahashi Toshimi, that immediately after the earthquake and tsunami, he had seen it struck by a fishing boat and washed out to sea. After crossing the Pacific, it arrived two years later on the shores of America. There must be some sort of karmic connection at work here. But the scars left in people’s hearts and minds by the disaster must be deep. So I wanted to sound out the local people on what they wanted to do. Takahashi-san was initially very reserved about the idea of returning the gate to Japan, but after a while he admitted that was what everyone really wanted. In the US, we’ve already had offers from several international shipping companies for assistance, and sometime in 2015 we expect to be able to return both torii to Japan or at least be preparing to do so.

The little shrine near the Okuki fishing port in Hachinohe that lost its torii.

This was all made possible by the people of Oregon who took such care with these unfamiliar objects from a distant place, and by the people of Japan who helped to search for the shrine parishioners. Shrine gates, Japanese gardens—in any case, what is important is the connection between the hearts and minds of individual people. It is my hope to continue to be a bridge between Japan and the US, and foster strong and enduring ties of this kind.

This interview was conducted in Japanese on November 27, 2014.

Interviewer: Sasayama Yuko (Program Department, International House of Japan)

Photographer (interview): Matsuzaki Nobusato

©2019 International House of Japan

To view other articles, click here.