At Tokyo’s Tsukiji Fish Market, you are immediately immersed in the lively cries of the workers and the traffic of “turret trucks” nimbly weaving their way through the crowds. Now, with the worldwide boom in Japanese cuisine, Tsukiji has literally become the world’s pantry. The market, however, is slated to move to a new location in Toyosu in the fall of 2016, and many already mourn the passing of its longtime home. We invited two experts with an abiding love for Tsukiji—a social anthropologist and a tuna trader who used to work at Tsukiji—to talk to us about its enduring attractions.

[June 2015]

Born in Illinois in 1951. Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University. In 1989 he began the research that would culminate in the publication of Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World (University of California Press, 2004; Japanese translation from Kirakusha in 2007), which has won a number of awards, including the Society of Economic Anthropology Best Book Award for 2006. His current research examines traditional Japanese food culture and the global popularity of Japanese cuisine.

Born in New York City in 1968. President of DML Venture Enterprises. Came to Japan in 1993 and, while still unfamiliar with Japanese culture, apprenticed for a year and a half with the tuna wholesaler Yamawa in Tsukiji. In 2000, he founded the tuna processing and export company DML and its brand Itsumo Foods. His activities have been introduced in the Japan Times and other venues.

Love at First Sight?

Theodore Bestor: I first encountered Tsukiji 30 years ago as a student. My wife and I were dirt poor, but somehow made friends with a local sushi chef. We’d ask him a lot of questions about fish and such, and one night he and his apprentices offered to take us to Tsukiji—which we’d never heard of before. We went on a lark, but it was like a trip to Mars [laughs]! I could hardly understand anything about what was going on. The atmosphere of the place completely blew my mind.

Then, maybe a decade later I was back in Tokyo to study the Japanese commercial distribution system, and I visited Tsukiji again, thinking to interview a few people. At that point my Japanese was much better, I had a more sophisticated sense of how Japanese society worked, and I just got sucked in. I felt like this was the most fascinating place in the world, so I immersed myself in research on Tsukiji and emerged in 2004 with a book.

David Leibowitz: I’ve read it, and it’s an honor to have this chance to talk about it with you in person. My encounter with Tsukiji was sort of haphazard. I was in the used clothing business here in Japan, but in about 1997 I became friends with this fresh tuna dealer and he took me to lunch in Tsukiji. As you say, it just blew my mind. The aroma of fish and the sea, the bustle and noise of the market, and the guys running around in every direction. There was something there for every one of the senses, and for me Tsukiji was love at first sight. So I just jumped feet first into this unknown world and spent a year and a half there apprenticing at a tuna wholesaler’s shop.

Tsukiji Fish Market handles over 2,000 tons of seafood every day. Some 30,000 people come daily to buy fresh seafood. (Photo courtesy of Yamawa Inc.)

A Glimpse of Edo Culture

Bestor: One of the things I love about Tsukiji is the people working there. The market is a tough job with terrible hours, but people are enjoying themselves. The auctioneers, the wholesalers, the chefs coming to buy fish directly—they laugh, they joke, they kid around. I think the unique culture and business practices of Tsukiji are rooted in the web of human relations built up in these day-to-day exchanges.

Leibowitz: I agree. Tsukiji is just overflowing with chaotic human energy. But in the midst of that chaos there is also a strange sense of order. I feel like it has something to do with the concept of bushido that was born out of the feudal system of the Edo period. There’s a hierarchy in which everyone knows their roles and responsibilities, for better or worse, and takes pride in doing their job to the best of their abilities.

Bestor: I don’t think of it as bushido, but, yeah, I’d say Tsukiji is one of the last vestiges of the Edo cultural tradition going back to the 17th century. One aspect of this is the kata, or forms, like in the Edo-period martial arts. There’s a proper way to do anything. For example, when you are carving up a tuna, the right way is for one apprentice to grab the hilt of the knife and the other to grab the end of the blade, wrapped in a towel—if they are not working together in harmony it’s very dangerous. Which is why mastering the basic kata is so important. The apprentice doesn’t just learn how to sharpen a knife—he learns how to sharpen it the right way. When choosing fish, the kata—the literal shape—of the fish is also quite important. Mismatches in size and proportions make them difficult to use in the kitchen; a crooked tail might mean the fish struggled violently when caught, and this will affect the flavor directly.

It requires three men to cut a tuna. (Photo courtesy of Yamawa Inc.)

Leibowitz: The eye the wholesalers have for fish is truly incredible. When I began working at Tsukiji I had no idea what it was they were looking at to determine the quality of the fish. They all looked the same to me [laughs]!

Bestor: The wholesalers don’t just know good from bad fish—they know exactly what level of quality their clients are looking for. They don’t just talk price or condition of the fish but say things like, “Yeah, this fish is really good, but it’s probably too expensive for your customers. This would be exactly what you want.” They understand their clients’ needs through daily communication, and respond to them faithfully. It’s not just a business transaction, it’s a relationship of trust. In fairly significant ways, such as this sort of give-and-take among tradespeople, what now is Tsukiji can be traced back to the Nihonbashi Fish Market that started in the early 18th century—a living inheritance of Edo culture.

Taking Life with Gratitude

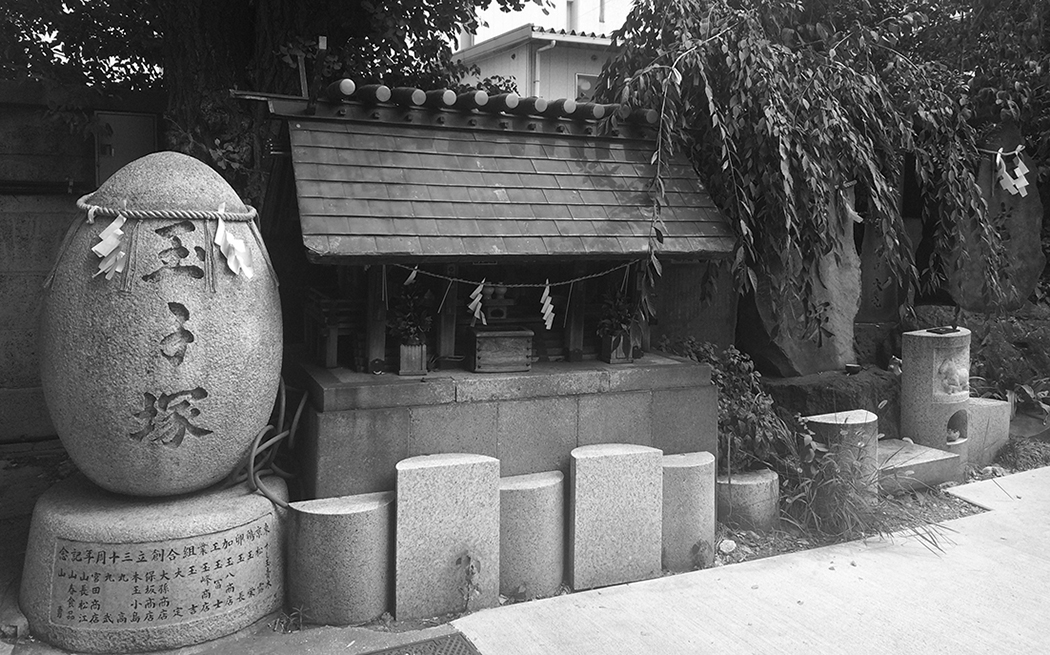

Bestor: In terms of Japanese cultural heritage, Namiyoke Shrine right beside the Tsukiji Market is a really fascinating place. On the grounds of the shrine there is a row of monuments to eggs, fish, shrimp, clams, sushi—and the people associated with the market stop by from time to time to pay their respects. There’s a sense of ethical engagement with other aspects of the living world—that in order to live, we must eat. And since in order to eat, we must take life, it should be done with respect and gratitude. This may be something unique to Japan. In Spain or in the United States you might find a Catholic shrine near the fish market, but that’s not for the fish, it’s for the fishermen—the men who lost their lives on the sea.

Monuments to eggs and seafood in Namiyoke Shrine. Memorial services are held for those foods throughout the year.

Leibowitz: In Judaism there is the practice of keeping kosher, which is really a body of laws and rules about how to treat animals ethically. In a sense, it’s similar to the Shinto idea of gratitude for the life we are taking from nature—the sense that there is a soul or spirit in forms of life other than the human, which is really interesting. In the West the desire to conquer and consume is strong. The mentality that says: I want some fish, there’s the fish, let’s go get the fish—even if it’s the very last one. In contrast the Japanese seem to me to have a stronger sense of coexisting with nature and being stewards of the environment.

Bestor: The Judeo-Christian religions essentially put humans above nature. If you look at the underlying philosophies of Shinto and traditional, preindustrial Japan there is much more of a sense that humans and nature are integrated. You see it in the Shinto celebration of the seasons, the periods of planting and harvest.

Leibowitz: I think the sense of harmony with nature and wanting to eat naturally is why the Japanese came up with the idea of eating sushi and sashimi.

Bestor: At least in North America the only kind of raw seafood I can think of that has traditionally been eaten is oysters. Many Western cuisines depend on cooking techniques, spices, and sauces to transform raw ingredients.

On the other hand, the basic principle of washoku—traditional Japanese cuisine—is that the underlying characteristics of the ingredients themselves should be self-evident. Traditionally, North Americans and Europeans have had little familiarity with the notion that eating seafood or animal products raw can be safe. I was born in central Illinois, which is over a thousand kilometers from the nearest seashore. If somebody had come up to me and said, “Here’s some rice and I put some really delicious raw fish on it, try it,” I would have run screaming from the house [laughs]. Sushi and sashimi are very recent things in North America, and in Europe as well, and the appreciation for raw seafood nowadays is a direct result of Japanese influence.

Washoku as a Vehicle of Japanese Culture

Bestor: In the past couple of decades, sushi and sashimi have been among the fastest growing food categories in the United States. Yet most of it is not being handled by trained Japanese chefs, with their eye for quality, and that’s a big problem. Sushi is not just slapping some raw fish on top of rice; the fundamentals of the traditional knowledge and craft that go into it aren’t getting properly transmitted.

I’ve met a number of people in the professional cooking world who now go on about umami, the fifth flavor. “I spent six weeks in Japan and all I did was make dashi [stock] and learn the difference between the types of konbu [kelp] I should use for it.” But these are guys who never even heard of konbu, dashi, or umami when they were in cooking school…

Leibowitz: It’s the same with the sanitary aspects: no matter how many rules you make, it seems impossible to get overseas Japanese restaurants to keep things as clean as a sushi restaurant in Japan. There has to be a cultural construct that informs people of how to handle raw food.

Bestor: My next book is going to be trying to explain what washoku is, as a projection of Japanese culture. Not just beautiful photographs and recipes, but in terms of all the cultural contexts that make Japanese cuisine a complete culinary system, ranging from traditional art and religious beliefs, to everyday etiquette and social interaction today. It is not just what you see on the plate in front of you—it’s the whole world!

Hopes and Fears of Relocation

Leibowitz: The Tokyo Metropolitan Government has decided to move the market to Toyosu, to reopen in the fall of 2016. But I hear a lot of longtime Tsukiji dealers are planning on quitting the business entirely due to the financial burden of the move. When I think about the loss of Tsukiji, this last vestige of Edo, I am heartbroken. And this is despite the fact that “Tsukiji” is like a brand name known around the world.

Bestor: Yes, it’s a shame how underappreciated Tsukiji is in terms of its cultural value as a specific place. Would someone move Hollywood to, say, Arizona, and rename it? No. The move of Tsukiji to Toyosu provokes that kind of shock. Though there are many things about the move I can understand: the physical plant of Tsukiji dates from 1935, so it’s getting pretty shabby. To me it’s kind of a nostalgic shabbiness, so I like it.

Shochiku is now shooting a film to make a record of Tsukiji, and I participated a little bit in making it.* Toyosu probably will be a cleaner, safer, more efficient working environment. I certainly hope that Toyosu is a success. I hope that people who have to move there continue to find it a satisfying place to work and that it continues to be able to supply the best seafood in the world to some of the best chefs in the world.

* The documentary film Tsukiji Wonderland (tentative) portraying the four seasons of Tsukiji and traditional Japanese food culture will be released by Shochiku Co., Ltd. (production and distribution) in 2016.

This dialogue was conducted on June 23, 2015.

Editing: International House of Japan, Program Dept.

Photographer (interview): Sato Nobutaka

©2019 International House of Japan

To view other articles, click here.