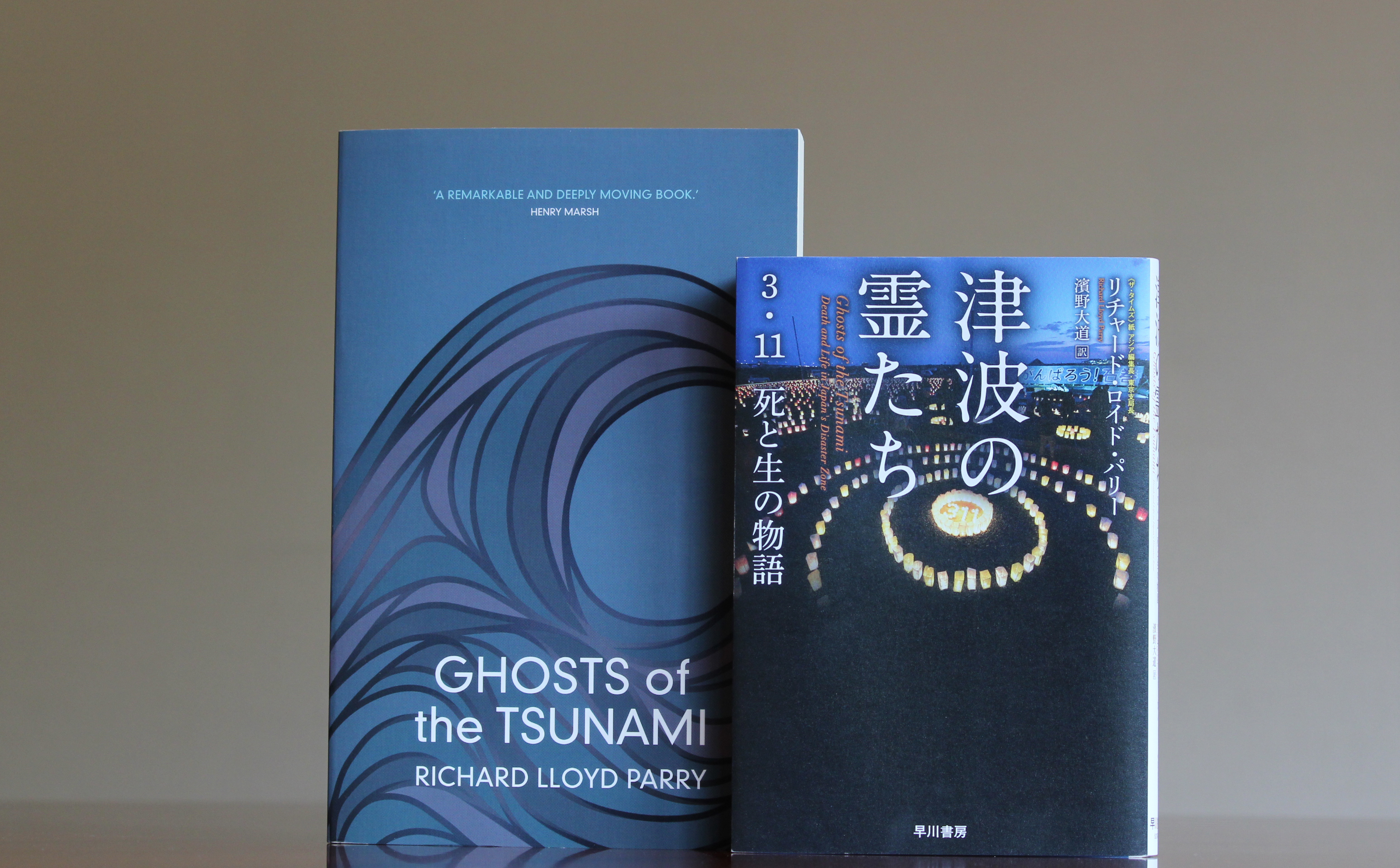

Richard Lloyd Parry, the Asia Editor and Tokyo Bureau Chief at The Times, has shined an illuminating journalistic light on Japanese society over his more than 20 years in the country. Lloyd Parry’s Ghosts of the Tsunami (2017), for example, immerses readers in a powerful, wrenching chronicle of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Probing the disaster through the tragic story of Okawa Primary School, where 74 of the 108 students either lost their lives or remain missing, he spent six years conducting research and writing the book. We sat down with Lloyd Parry to talk more about the work, his role as a journalist, and his perspective on Japan.

[March 2018]

Born in Merseyside, England, in 1969, Lloyd Parry is currently the Asia Editor and Tokyo Bureau Chief for The Times (UK). After graduating from Oxford University, he eventually moved to Japan to work as a foreign correspondent for The Independent in 1995 and later started his career at The Times in 2002, covering Japan, the Korean Peninsula, and Southeast Asia. He has now lived in Japan for over 20 years. Lloyd Parry’s works include People Who Eat Darkness: The Fate of Lucie Blackman, a book that chronicles British national Lucie Blackman’s disappearance from Tokyo, and Ghosts of the Tsunami, which won the Rathbones Folio Prize.

In Ghosts of the Tsunami, Lloyd Parry grounds his journalistic narrative in the story of Okawa Primary School in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture. Abutting foothills, surrounded by rice fields, and not far from the mouth of the Kitakami River, the school had easy access to nearby evacuation sites—but the students remained in the schoolyard, going methodically through the standard protocol, until the tsunami washed them away. Ghosts of the Tsunami weaves its painstaking portrait around what happened that day at the school, using scores of interviews and personal testimony to examine the background, the battle between the administration and the children’s families, the friction among families, and the families’ lawsuit against the prefectural and city governments. Lloyd Parry also focuses on the various psychic phenomena that started emerging in the wake of the disaster: a taxi driver giving rides to “ghost passengers,” a mother who asked a medium to help find her child’s remains. The heartbreak coursing through those personal accounts takes on a powerful, resonant dimension in Lloyd Parry’s empathetic prose, leaving a lasting impression on readers.

Your latest work, Ghosts of the Tsunami, has been released in the United Kingdom, the United States, and, in January 2018, Japan. How has the response been?

I think the reaction has been pretty good so far. The story of Okawa Primary School is pretty unknown outside Japan, and stories of ghosts and hauntings are very new to people. I wrote the book for a foreign audience and people who don’t know Japan, so I was a bit nervous about how it would go over with Japanese audiences in translation. It turned out, though, that people adopted the perspective of a foreigner in reading it—Japanese readers, including the people we interviewed for the book, have been warm and appreciative, which is a great relief. The French edition of the book will be published in March, with a Vietnamese edition coming out after that.

What made you write the book? You obviously went deep into your coverage, delving into the details of the Okawa Primary School story to uncover some compelling issues.

I wrote some articles right after the disaster struck on March 11 because I was reporting on it for The Times, but I recognized early on that really capturing the gravity of the event was one of those things that’s very difficult to do justice to in short newspaper journalism. I knew the story would lend itself to a longer treatment in a book. It took me a long time to find the right angle of approach, though, because I knew I couldn’t produce a book about the whole disaster. It was a few months before I learned about Okawa Primary School and the stories of the ghosts. After doing some reporting for over a year, it wasn’t till the end of 2012 that I decided to write a book. My approach in writing a book has always been to try to find smaller stories that enable you to thereby tell the larger story. In 2012, I’d finally identified the stories. It wasn’t an easy process; I had to muster my own courage to write because they’re heartbreaking stories. When you embark on a book, you have to immerse yourself in these stories for years. It took me a while to decide that I was ready to do that.

The impact of the nuclear disaster was probably a topic that a lot of Western readers were interested in. Why did you decide to focus on Okawa Primary School and ghost stories, then?

I made the conscious choice to avoid the nuclear disaster as much as possible. The Fukushima meltdown itself was a terrible disaster and, I believe, a crime. In my country, Britain, we don’t have earthquakes or tsunamis, but we do have nuclear power stations. So people see them as a danger much closer to them. But it remains true that, although so many people died as an indirect result of the evacuation, nobody has died as a direct result of the nuclear plant. The tsunami, on the other hand, claimed 18,500 lives. Okawa Primary School is one tragedy of many, one that killed 74 children and 10 teachers. It was the only elementary school where the tsunami claimed this many lives. The fact that it was a school, one of those places you just assume to be safe, and in Japan, a country where people are so aware of disaster preparedness, and the fact these children were so young and they all died together and it was completely avoidable, make it one of the worst stories in the whole tragedy, I think.

The other big part of the book is the psychic, spiritual component, something I only learned about six months after the disaster when I started hearing about ghost sightings across the Tohoku region, hauntings, and priests performing exorcisms. After the tumult of the disaster has settled down a bit and everyone has enough to eat, has shelter, and has their minimum resources, that’s when people finally start to reflect on the whole experience. That’s when trauma and PTSD start to manifest themselves—and also when the ghosts begin to appear. Tohoku is rich in folklore and superstition, like the Tono monogatari and itako shamanism, which makes it less surprising that the manifestations should be felt. In Tohoku, the world of the dead is always closer. I was talking to a Japanese academic recently, and he made the point that people didn’t see ghosts after the Kobe earthquake or the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II—there were far greater losses of life in those disasters, but nobody was talking about seeing ghosts. I don’t believe in ghosts or the supernatural, personally, but that’s not the important thing. The key is that, for these people who do encounter the supernatural, the experiences are very real. They’re symbols of the massive trauma that the Tohoku region and the whole culture of Japan—not just the people who experienced the terror of the tsunami head-on—experienced. As I was writing the book, I wanted to bring out the fact that the cost of the disaster was as much mental as it was physical.

You’ve lived in Tokyo for more than 20 years now. Have you noticed any changes in Tokyo life over the seven years since the March 11 disaster?

I assume that people have learned practical lessons; I’m sure, for example, that pretty much every school in the country has double-checked its disaster manual by now. Tokyo could be hit by a massive earthquake at any moment. If it were to happen next week, more people would undoubtedly evacuate more quickly. Yet, we live here in Tokyo, day to day, as if everything is fine. Everyday life hasn’t really changed. The city transformed for a few weeks after March 11 because there were basically no lights on under the emergency energy-saving campaign. It didn’t feel like Tokyo then—but it’s just gone back to normal now. When it comes to nuclear power, I think you can say that people haven’t learned enough lessons. I think there’s a big question about whether Japan should have any nuclear power at all because the country is so vulnerable to tsunamis, earthquakes, and volcanoes. Japan needs to debate that issue more actively, more vigorously.

As a foreign journalist working in Japan, do you ever sense any differences between British journalism and Japanese journalism?

I can’t speak for Japanese journalism as a whole, obviously, but I get the feeling that journalists and newspapers here do their jobs differently from how I do my journalistic work. British journalists and big-name newspapers take pride in being troublemakers, agents of resistance against the people in power. That’s our job—but we don’t cause trouble just for the sake of it. If I, as a reporter, can expose the wrongdoings of a big company or powerful politician, using the facts to set things straight, that’s something to be very proud of. Although there are certainly exceptions, I think most of the Japanese media is actually pretty passive about criticizing the institutions in power. It might have something to do with the whole social dynamic of avoiding confrontation, I suppose.

What got you into journalism?

I got interested in journalism when I was at university. I’d always liked writing and traveling, so starting your career as a foreign correspondent is the best thing you can do if those are your interests. Different journalists like different things, of course. Personally, I like writing; I like sitting on my own and just putting words together as well as I can. I like the excitement of reporting, too. These days, there’s so much information pervading extremely accessible sources like the Internet and broadcast television; you can just talk to people and get the information you’re looking for. The most fulfilling thing, though, is when something big happens and you don’t quite know what’s transpired until you actually go out to the place and report on what you see. The March 11 disaster was a case in point. That real-time, illuminating coverage is the original job of a reporter, but those kinds of experiences are surprisingly rare these days.

Despite all the probing, high-quality articles and books coming out, there’s a growing sense that people these days aren’t reading as much anymore. Do you share those concerns?

It’s certainly true that social media and the devices in our pockets encourage short attention spans, in some way leading people to stay away from longer articles. Still, I see some reaction against that trend, too. The article that Ghosts of the Tsunami grew out of was a particularly long one: it probably took around 45 minutes to read it online. Despite that length, people shared it all over the place. You can find penetrating, high-quality content in lots of different media, including online sources. With the Internet full of so many little nuggets of information, headlines and snippets that give you the gist of the content in bite-size pieces, people might actually be developing more of an appetite for longer, more in-depth pieces. There’s an American website called Longreads, which links to a whole host of longer, higher-quality journalistic content. I’ve always preferred to write narratives that step back and tell a story from an objective standpoint, so I don’t mind if things get long; to me, it’s best to tell individual, human stories in close, personal detail and then generalize the bigger picture out of that.

Some media outlets have either closed or downsized their Tokyo offices over the last 10 years. How do you think the foreign media sees Japan?

The Times, the New York Times, and the Financial Times all still have offices in Tokyo. For newspapers, Japan is a crucial place for reporting the news to the world. I cover North Korea, South Korea, and Southeast Asia, too, and the Korean Peninsula and China have obviously been garnering quite a bit of attention. That said, Japan is still so important because of the size of its economy, because of its vital diplomatic position, because it’s the base for a large number of US troops, and also because of its cultural significance.

* * * * *

On April 26, the Sendai High Court ruled that the deaths of Okawa Primary School pupils in the March 11 disaster could have been prevented if the city of Ishinomaki and Miyagi Prefecture had updated their contingency plan. The court ruled the two local governments should pay 1.43 billion yen (13.7 million dollars) to the parents of 23 children who filed the lawsuit. The local governments have taken the case to the Supreme Court.

What are your thoughts on the current situation?

This is really sickening. The city and the prefecture should have accepted the original verdict, rather than prolonging the agony of the families of the dead school children with another appeal. On the other hand, even a financial award such as this is going to do very little, if anything, to assuage the grief that they feel. The March 11 disaster isn’t over. More translations of Ghosts of the Tsunami are going to be coming out, so I think I’ll have more opportunities to talk about the disaster. I want to keep the dialogue going, to keep the issues alive and relevant in popular consciousness around the world.

This interview was conducted on March 20, 2018.

Interviewers: Ozawa Miwako, Sasayama Yuko (Program Department, International House of Japan)

Photographer (interview): Kodera Kei

©2019 International House of Japan

To view other articles, click here.